Image 1 of 10

Image 1 of 10

Image 2 of 10

Image 2 of 10

Image 3 of 10

Image 3 of 10

Image 4 of 10

Image 4 of 10

Image 5 of 10

Image 5 of 10

Image 6 of 10

Image 6 of 10

Image 7 of 10

Image 7 of 10

Image 8 of 10

Image 8 of 10

Image 9 of 10

Image 9 of 10

Image 10 of 10

Image 10 of 10

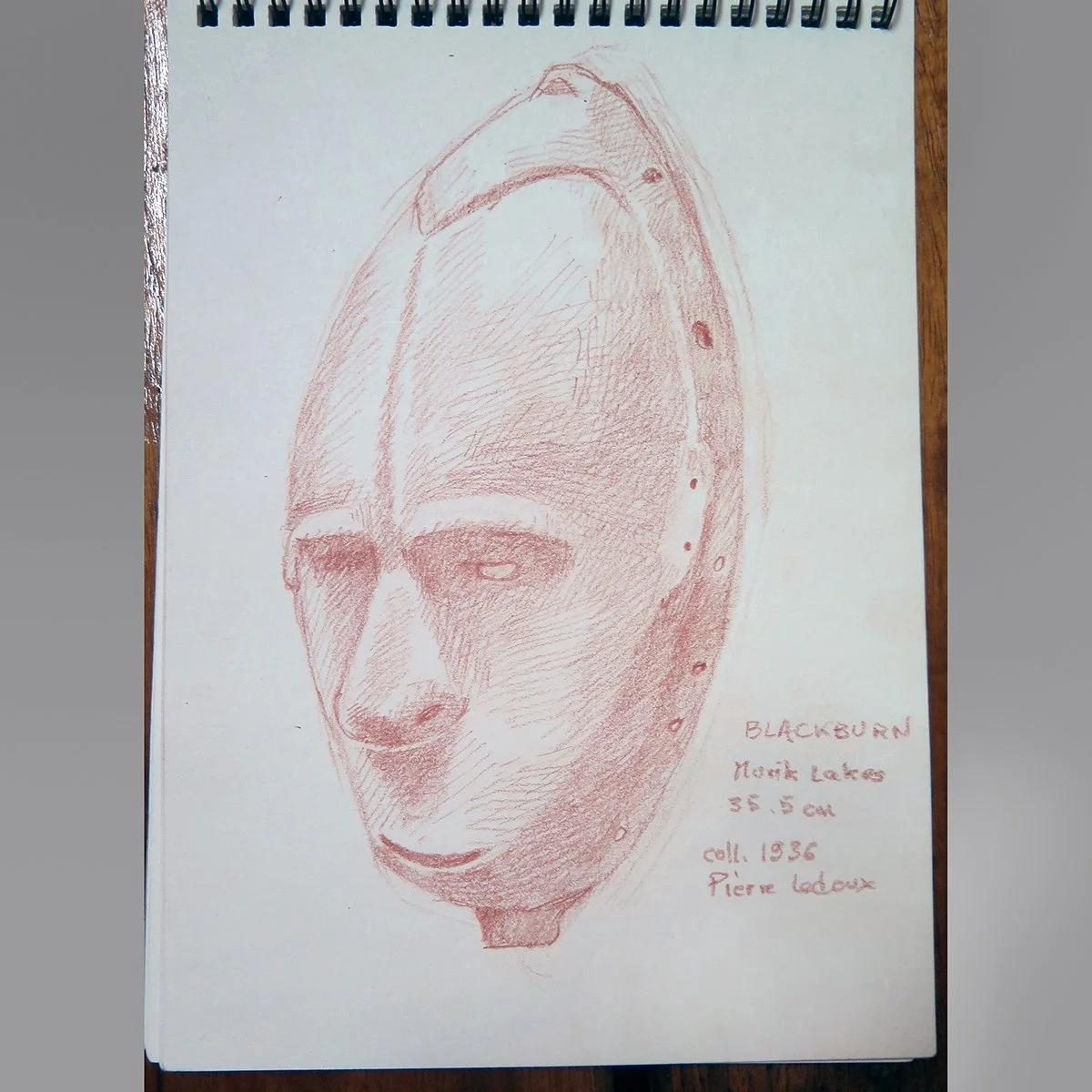

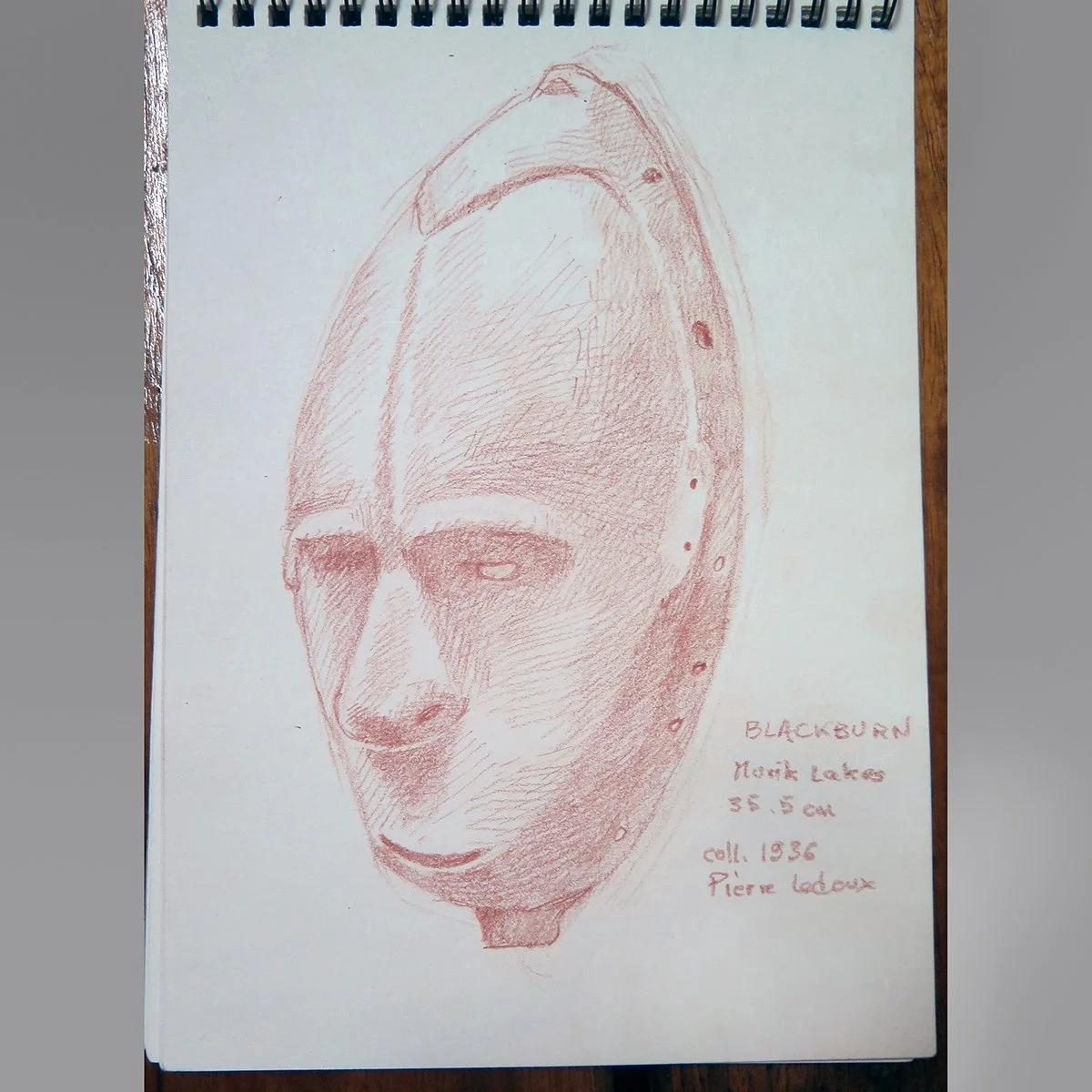

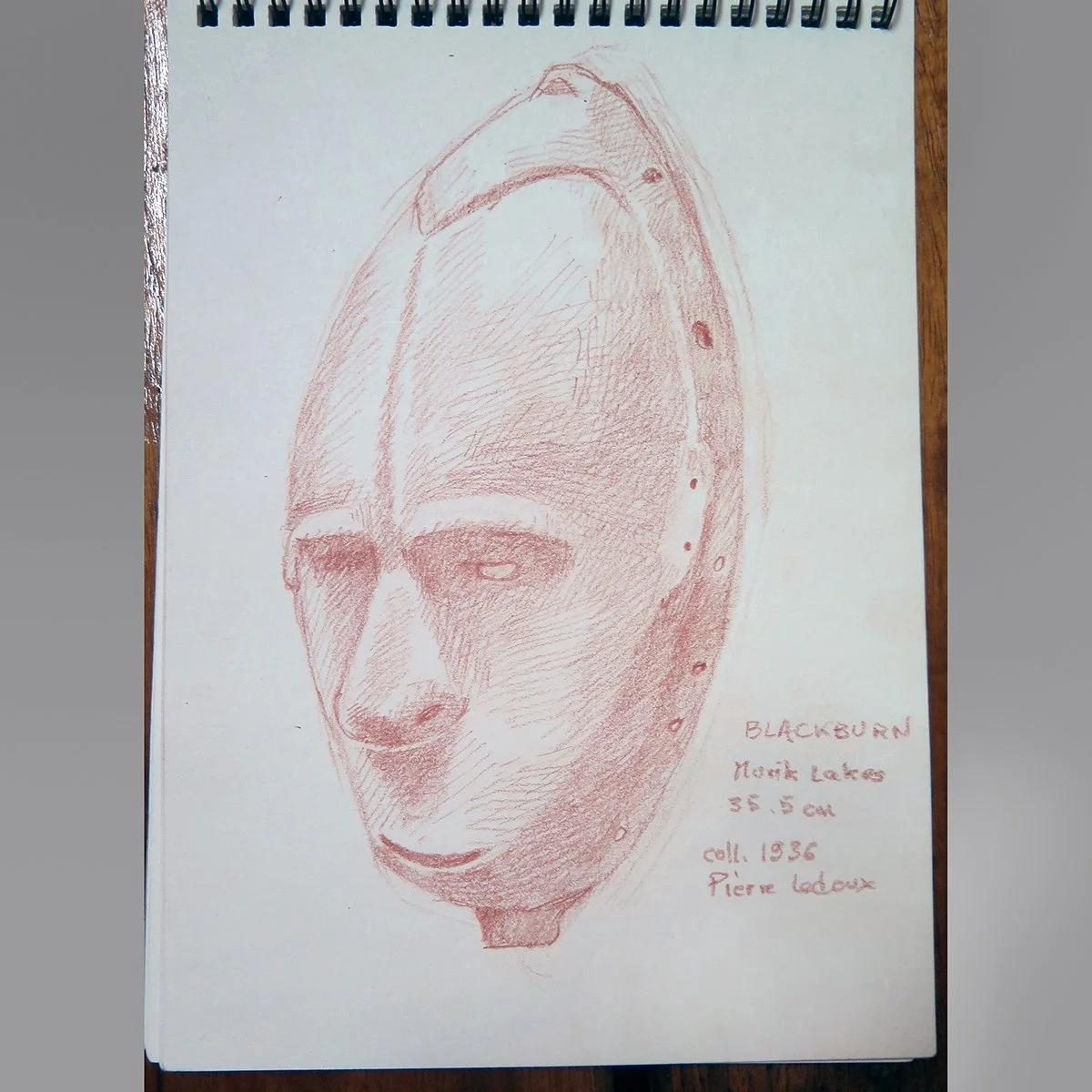

Powerful Murik Lakes Pre-Contact Mask - SOLD

Murik Lakes, Coastal Sepik River basin, Papua New Guinea

Wood, traces of ocher pigments

Early 19th century

Height 14 inches (35.5 cm)

Provenance: Field collected in the Murik Lakes region in 1936 by Louis Pierre Ledoux. By descent to Joan Ledoux until 2015.

Exhibited: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Art of the South Seas, January 29 – May 19, 1946.

Living along the Murik Lakes, a series of coastal lagoons near the mouth of the Sepik River, the Murik people were accomplished carvers and produced some of the most powerful statuary and masks known from New Guinea. These objects, exchanged with neighboring peoples as part of regional trade networks, are believed to have been widely influential in the broader development of sculpture in Lower Sepik basin. According to oral tradition, the Murik were granted their skills in wood carving from the two brothers Andena and Dibadiba, ancient cultural heroes who descended the Sepik River in a canoe and taught the people how to carve. This art of carving was passed down only within certain families, with the novice carver apprenticed to his father or uncle, and later taught more specialized skills from the community’s master carvers. Murik artists strived for perfection in their works, and tradition encouraged others within the community to express their criticism or approval of the carver’s skills by describing the work as aretogo “beautiful”, or maogo “ugly”, or by making statements such as tosiyan “stands out well”. An inventive carver may be praised for his nonon or imagination. However, it was not merely the visual properties, such as the sculptural harmony or presence of the carved image that were judged, but rather the supernatural power, or maneng, imparted to the sculpture by the artist that was of foremost importance. Murik carvers ritually infused the sacred images with maneng using magical leaves placed over their eyes and reciting specific incantations, or timits, during the carving process.

Masks were a central element of male religious life among the Murik. Dance masks typically representing powerful spirits or important ancestors were used in a diversity of ceremonial contexts, either worn directly on the face or, in many instances, attached to a larger basketry framework placed over the wearer’s head. Because the masks required skill and conscious intention, and most importantly spiritual inspiration to create, they were treated with great respect and care. To avoid unintentionally or negatively bringing forth their power, custodians secured the masks in secluded spaces within the men’s house, where over time the surfaces developed a darkened patina from the ever-present smoke of small cooking fires.

Skillfully carved without the use of metal tools, the mask presented here powerfully portrays an important clan founder. The archaic visage exudes a commanding presence manifest only in the earliest examples of Murik Lakes sculpture, born from an intensity of artistic and spiritual expression intended to honor the ancestors. Perhaps the closest comparisons can be made with the powerful faces portrayed in pre-contact Murik kandimbong ancestor statuary, thought to represent stylized amplifications of ancestor skulls. Like other early examples, the mask is rendered in deep voluminous form, the carefully hollowed interior spaces intended to make room for the occupying spirit and to effectively contain its potent animating energy. The large, rounded forehead is divided into two swollen lobes bisected by a medial ridge that extends down to the tip of the nose, inside which the septum is pierced, in reference to the mythical hero Andena, whose nose was struck with a pronged fishing spear during a fight. The nostrils of the Murik people themselves were pierced, as were the ears, decorated as an outward sign of their identification with such mythical ancestors. The ears on the mask are accordingly pierced by a pair of suspension holes and the perimeter of the mask additionally features a series of fifteen attachment holes, used to secure the mask to its accompanying basketry framework. A close inspection of the ancient surface reveals the exclusive use of stone and shell adzes in the carving of the mask, and the additional use of rodent or flying fox tooth chisels to perforate the mask’s surface, with traces of red ocher visible inside the perforated holes. Metal blades only first became available along the Coastal Sepik region after 1900 and further upstream among the Iatmul only after 1908. The use of indigenous stone and shell tools impacted the modelling of pre-contact Murik Lakes masks and figures as the carved features tended to be more subtle, fluid, and less rigid, with the faces feeling more organic than mechanical. The patina of the mask additionally reveals a deep generational history, consisting of repeated cycles of ceremonially applied ocher, heavy smoke encrustations, ritual cleanings and reinitiations.

The mask boasts a distinguished early provenance, having been field collected by anthropologist Louis Pierre Ledoux in 1936. Graduating from Harvard University in 1935, Ledoux immediately started searching for opportunities to travel and study distant primitive cultures.One day in late October 1935, after having wandered the halls of the American Museum of Natural History, Ledoux received a message that the renown Dr. Margaret Mead, who was the museum’s curator at the time, had requested a meeting with him.Immediately after introductions Mead told him “You go there, and you go alone” as she pointed to a map of Papua New Guinea. Ledoux would soon after be travelling to the village of Kaup, in the Murik Lakes region. His fieldwork, encompassing a five-month period from February to June 1936, was intended to study the traditional trade networks of the region.After a short stay in Australia to secure the necessary equipment and provisions, Ledoux, accompanied by and an incredible sixty-nine wooden crates, disembarked at the village of Sumup, along New Guinea’s coast on February 13th, 1936.From there it was a mere seven-mile hike to his final destination in the village of Kaup. Ledoux had gone into the field with the general objective of studying indigenous trade networks, however he soon found himself recording, observing, photographing, and attempting to understand the daily lifestyle, relationships, and oral histories of the Murik people. It is not clear what steered his collecting agenda, though he did focus his efforts on collecting important and irreplaceable artifacts that the local catholic priest Father Schmidt, had asked him to collect and care for, lest they soon be burned by the local missionaries.Ledoux later wrote that he in fact intercepted a local missionary about to burn of an entire attic full of important Murik artifacts that had been recently removed from nearby villages.In addition to these artifact rescue missions, Ledoux also received a number of important artifacts from Father Schmidt, discreetly given to the young anthropologist with the understanding that their safekeeping was now his responsibility. Ledoux later wrote particularly fondly and respectfully of Father Schmidt, who had been living among the Murik for decades and had established wonderful relations with them. A significant figure in the history of the Murik people, Father Joseph Schmidt had arrived in New Guinea two decades earlier in 1913, under the patronage of the Catholic mission – The Society of the Divine Word. Unlike neighboring missionaries, Schmidt did not outright dismiss earlier Murik religious beliefs but recorded them faithfully and collected many sacred carvings. Schmidt was present when German troops landed at Kaup and proceeded through the Murik villages, burning the men’s houses and destroying many ancient and sacred objects as punishment for an earlier Murik head-hunting raid. It was likely these devastating events that inspired Schmidt’s heroic efforts to preserve as much of the ancient material culture as he was able. Indeed, he can be credited with providing us with some of the most important masterpieces from the Murik Lakes region, as well as producing an important ethnographic study of the Murik people titled “Die Ethnographie der Nor-Papua (Murik-Kaup-Karau) bei Dallmannhafen, Neu-Guinea” published in 1926. It is quite likely that this ancient mask was one of the objects originally obtained by Father Schmidt and given to Ledoux to care for.Father Schmidt’s deep understanding of Murik culture had provided him with a discerning eye when selecting objects of the greatest cultural significance for protection and preservation.

Upon his return to the United States, Ledoux successfully presented his collection of 279 Coastal Sepik objects to the American Museum of Natural History and was later named a patron of the museum. Other museums he presented objects to include the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard and later the Brooklyn Museum. Ledoux also presented to A.P. Elkin at the University of Sydney a small but select collection, some of which were featured at the 2015 “Myth and Magic, Art of the Sepik River” exhibition at the national Gallery of Australia, in Canberra. Ledoux had also retained a number of cherished Murik Lakes objects for his personal collection, and for a period this remarkable stone-carved mask along with several others were displayed in his office in New York. Rene d’Harnoncourt, the curator and later director for New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), approached Ledoux with a request that several of the Murik Lakes masks in his collection be included in an important oceanic art exhibition being assembled at the museum. That landmark exhibition titled “Arts of the South Seas” opened at MOMA on January 29th, 1946, and continued until June 19th of that year. The remarkable Murik Lakes mask presented here, alongside several others on loan from Ledoux, can be seen on display in archived photographs, including a rare early color image.

Ancient New Guinea artifacts that have survived to speak to us today are imbued with powerful and otherworldly stories, most of which are lost and which we can only begin to imagine. The Murik artist who created this mask nearly two centuries ago leaves to us no written records describing the world as he experienced it. Yet, the artist still speaks to us. As stone tools were neither sharp nor efficient, the carver worked patiently, bit by bit, and moved over the wood slowly with prolonged spiritual reflection and artistic deliberation. This intensive creative process, which could take a month or longer to complete, resulted in a tangible material representation of the remote ancestral spirit very much alive in the artist’s mind, and permits us a glimpse into the artist’s magical and primeval inner world. Accompanying this mask are also the living histories of Father Joseph Schmidt’s remarkable time among the Murik in New Guinea and of the young and adventurous Louis Ledoux, who intriguingly had retained this mask for sixty-five years until his eventual passing in 2001.

Murik Lakes, Coastal Sepik River basin, Papua New Guinea

Wood, traces of ocher pigments

Early 19th century

Height 14 inches (35.5 cm)

Provenance: Field collected in the Murik Lakes region in 1936 by Louis Pierre Ledoux. By descent to Joan Ledoux until 2015.

Exhibited: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Art of the South Seas, January 29 – May 19, 1946.

Living along the Murik Lakes, a series of coastal lagoons near the mouth of the Sepik River, the Murik people were accomplished carvers and produced some of the most powerful statuary and masks known from New Guinea. These objects, exchanged with neighboring peoples as part of regional trade networks, are believed to have been widely influential in the broader development of sculpture in Lower Sepik basin. According to oral tradition, the Murik were granted their skills in wood carving from the two brothers Andena and Dibadiba, ancient cultural heroes who descended the Sepik River in a canoe and taught the people how to carve. This art of carving was passed down only within certain families, with the novice carver apprenticed to his father or uncle, and later taught more specialized skills from the community’s master carvers. Murik artists strived for perfection in their works, and tradition encouraged others within the community to express their criticism or approval of the carver’s skills by describing the work as aretogo “beautiful”, or maogo “ugly”, or by making statements such as tosiyan “stands out well”. An inventive carver may be praised for his nonon or imagination. However, it was not merely the visual properties, such as the sculptural harmony or presence of the carved image that were judged, but rather the supernatural power, or maneng, imparted to the sculpture by the artist that was of foremost importance. Murik carvers ritually infused the sacred images with maneng using magical leaves placed over their eyes and reciting specific incantations, or timits, during the carving process.

Masks were a central element of male religious life among the Murik. Dance masks typically representing powerful spirits or important ancestors were used in a diversity of ceremonial contexts, either worn directly on the face or, in many instances, attached to a larger basketry framework placed over the wearer’s head. Because the masks required skill and conscious intention, and most importantly spiritual inspiration to create, they were treated with great respect and care. To avoid unintentionally or negatively bringing forth their power, custodians secured the masks in secluded spaces within the men’s house, where over time the surfaces developed a darkened patina from the ever-present smoke of small cooking fires.

Skillfully carved without the use of metal tools, the mask presented here powerfully portrays an important clan founder. The archaic visage exudes a commanding presence manifest only in the earliest examples of Murik Lakes sculpture, born from an intensity of artistic and spiritual expression intended to honor the ancestors. Perhaps the closest comparisons can be made with the powerful faces portrayed in pre-contact Murik kandimbong ancestor statuary, thought to represent stylized amplifications of ancestor skulls. Like other early examples, the mask is rendered in deep voluminous form, the carefully hollowed interior spaces intended to make room for the occupying spirit and to effectively contain its potent animating energy. The large, rounded forehead is divided into two swollen lobes bisected by a medial ridge that extends down to the tip of the nose, inside which the septum is pierced, in reference to the mythical hero Andena, whose nose was struck with a pronged fishing spear during a fight. The nostrils of the Murik people themselves were pierced, as were the ears, decorated as an outward sign of their identification with such mythical ancestors. The ears on the mask are accordingly pierced by a pair of suspension holes and the perimeter of the mask additionally features a series of fifteen attachment holes, used to secure the mask to its accompanying basketry framework. A close inspection of the ancient surface reveals the exclusive use of stone and shell adzes in the carving of the mask, and the additional use of rodent or flying fox tooth chisels to perforate the mask’s surface, with traces of red ocher visible inside the perforated holes. Metal blades only first became available along the Coastal Sepik region after 1900 and further upstream among the Iatmul only after 1908. The use of indigenous stone and shell tools impacted the modelling of pre-contact Murik Lakes masks and figures as the carved features tended to be more subtle, fluid, and less rigid, with the faces feeling more organic than mechanical. The patina of the mask additionally reveals a deep generational history, consisting of repeated cycles of ceremonially applied ocher, heavy smoke encrustations, ritual cleanings and reinitiations.

The mask boasts a distinguished early provenance, having been field collected by anthropologist Louis Pierre Ledoux in 1936. Graduating from Harvard University in 1935, Ledoux immediately started searching for opportunities to travel and study distant primitive cultures.One day in late October 1935, after having wandered the halls of the American Museum of Natural History, Ledoux received a message that the renown Dr. Margaret Mead, who was the museum’s curator at the time, had requested a meeting with him.Immediately after introductions Mead told him “You go there, and you go alone” as she pointed to a map of Papua New Guinea. Ledoux would soon after be travelling to the village of Kaup, in the Murik Lakes region. His fieldwork, encompassing a five-month period from February to June 1936, was intended to study the traditional trade networks of the region.After a short stay in Australia to secure the necessary equipment and provisions, Ledoux, accompanied by and an incredible sixty-nine wooden crates, disembarked at the village of Sumup, along New Guinea’s coast on February 13th, 1936.From there it was a mere seven-mile hike to his final destination in the village of Kaup. Ledoux had gone into the field with the general objective of studying indigenous trade networks, however he soon found himself recording, observing, photographing, and attempting to understand the daily lifestyle, relationships, and oral histories of the Murik people. It is not clear what steered his collecting agenda, though he did focus his efforts on collecting important and irreplaceable artifacts that the local catholic priest Father Schmidt, had asked him to collect and care for, lest they soon be burned by the local missionaries.Ledoux later wrote that he in fact intercepted a local missionary about to burn of an entire attic full of important Murik artifacts that had been recently removed from nearby villages.In addition to these artifact rescue missions, Ledoux also received a number of important artifacts from Father Schmidt, discreetly given to the young anthropologist with the understanding that their safekeeping was now his responsibility. Ledoux later wrote particularly fondly and respectfully of Father Schmidt, who had been living among the Murik for decades and had established wonderful relations with them. A significant figure in the history of the Murik people, Father Joseph Schmidt had arrived in New Guinea two decades earlier in 1913, under the patronage of the Catholic mission – The Society of the Divine Word. Unlike neighboring missionaries, Schmidt did not outright dismiss earlier Murik religious beliefs but recorded them faithfully and collected many sacred carvings. Schmidt was present when German troops landed at Kaup and proceeded through the Murik villages, burning the men’s houses and destroying many ancient and sacred objects as punishment for an earlier Murik head-hunting raid. It was likely these devastating events that inspired Schmidt’s heroic efforts to preserve as much of the ancient material culture as he was able. Indeed, he can be credited with providing us with some of the most important masterpieces from the Murik Lakes region, as well as producing an important ethnographic study of the Murik people titled “Die Ethnographie der Nor-Papua (Murik-Kaup-Karau) bei Dallmannhafen, Neu-Guinea” published in 1926. It is quite likely that this ancient mask was one of the objects originally obtained by Father Schmidt and given to Ledoux to care for.Father Schmidt’s deep understanding of Murik culture had provided him with a discerning eye when selecting objects of the greatest cultural significance for protection and preservation.

Upon his return to the United States, Ledoux successfully presented his collection of 279 Coastal Sepik objects to the American Museum of Natural History and was later named a patron of the museum. Other museums he presented objects to include the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard and later the Brooklyn Museum. Ledoux also presented to A.P. Elkin at the University of Sydney a small but select collection, some of which were featured at the 2015 “Myth and Magic, Art of the Sepik River” exhibition at the national Gallery of Australia, in Canberra. Ledoux had also retained a number of cherished Murik Lakes objects for his personal collection, and for a period this remarkable stone-carved mask along with several others were displayed in his office in New York. Rene d’Harnoncourt, the curator and later director for New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), approached Ledoux with a request that several of the Murik Lakes masks in his collection be included in an important oceanic art exhibition being assembled at the museum. That landmark exhibition titled “Arts of the South Seas” opened at MOMA on January 29th, 1946, and continued until June 19th of that year. The remarkable Murik Lakes mask presented here, alongside several others on loan from Ledoux, can be seen on display in archived photographs, including a rare early color image.

Ancient New Guinea artifacts that have survived to speak to us today are imbued with powerful and otherworldly stories, most of which are lost and which we can only begin to imagine. The Murik artist who created this mask nearly two centuries ago leaves to us no written records describing the world as he experienced it. Yet, the artist still speaks to us. As stone tools were neither sharp nor efficient, the carver worked patiently, bit by bit, and moved over the wood slowly with prolonged spiritual reflection and artistic deliberation. This intensive creative process, which could take a month or longer to complete, resulted in a tangible material representation of the remote ancestral spirit very much alive in the artist’s mind, and permits us a glimpse into the artist’s magical and primeval inner world. Accompanying this mask are also the living histories of Father Joseph Schmidt’s remarkable time among the Murik in New Guinea and of the young and adventurous Louis Ledoux, who intriguingly had retained this mask for sixty-five years until his eventual passing in 2001.